Agricultural productivity growth is and will continue to be at the core of strengthening sustainable agricultural systems.

Indeed, improved efficiency of input and natural resource use has been increasingly emphasized as the single most effective solution to simultaneously achieving production and environmental goals. Changes in TFP also reveal how well our agricultural knowledge and innovation systems (AKIS) are reaching and supporting producers at all scales of production to improve productivity. An increase in TFP growth suggests that an increasing number of producers are adopting, at minimum, scientifically proven, contextually- and scale-appropriate tools—such as technologies, strategies, and practices—that improve the sustainable use of scarce resources, including nonrenewables.

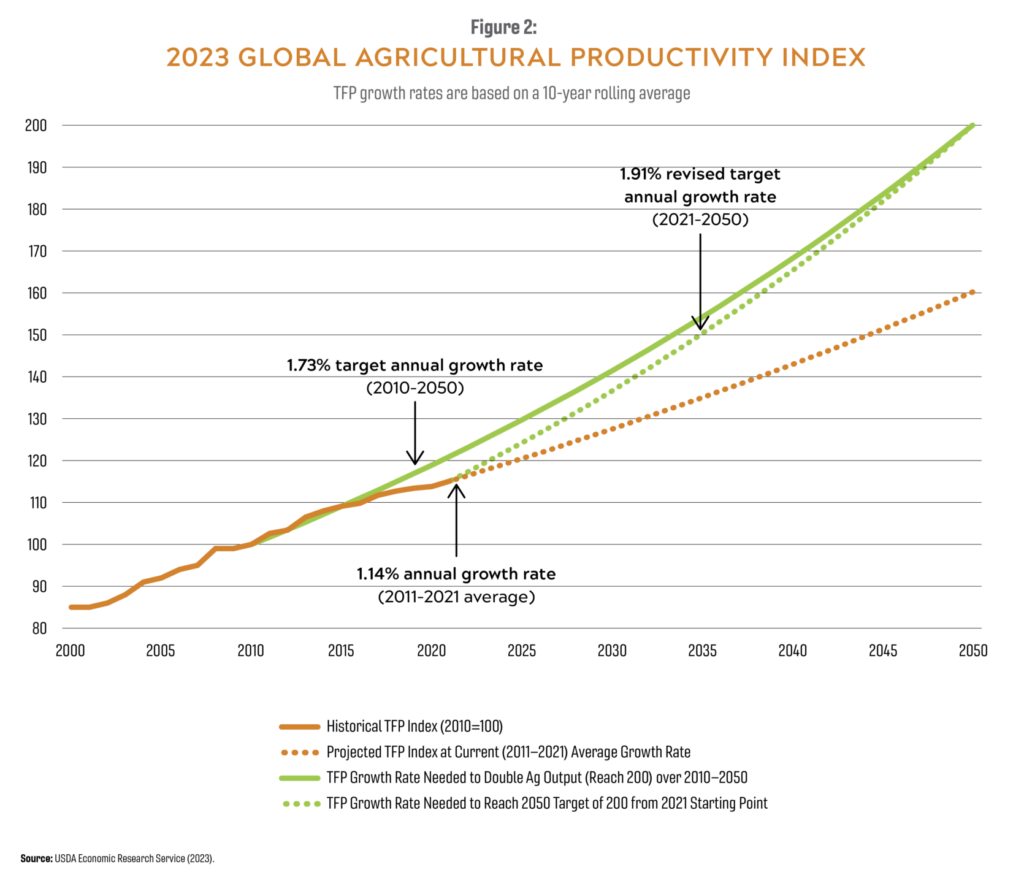

When the GAP Report® was first published in 2010, the “GAP Index” was established to track changes in TFP growth and to illustrate the future growth necessary—holding inputs constant—to sustainably fulfill global needs for agricultural products by 2050. The GAP Index target, which was a projected rate of 1.73 percent average annual TFP growth during 2010–2050 (solid green line, Figure 2), was based on the assumption that agricultural outputs would need to double between 2010 and 2050 to support a projected population of 10 billion people.

Measured as total factor productivity (TFP), agricultural productivity growth is achieved when producers increase their output of crops, livestock, or aquaculture products, using the same amount or less land, labor, capital, fertilizer, feed, and livestock. In other words, TFP rises when producers utilize innovative agricultural technologies or labor and efficiency practices to increase output with the same amount or fewer resources (Figure 1).

Tracking changes in TFP growth reveals a bigger picture of how well agricultural production is able to contribute to pressing global issues such as poverty alleviation, food security and nutrition improvements, and environmental externality reduction (Rahman et al., 2022). For example, TFP growth can lead to increased competitiveness in the sector through lower production costs. A one percent increase in productivity growth is equivalent to a one percent decrease in the cost of producing, storing, and selling one unit of a particular product. Consumers also benefit from TFP growth since the per-unit price for producers moves through the value chain, influencing the prices consumers pay.